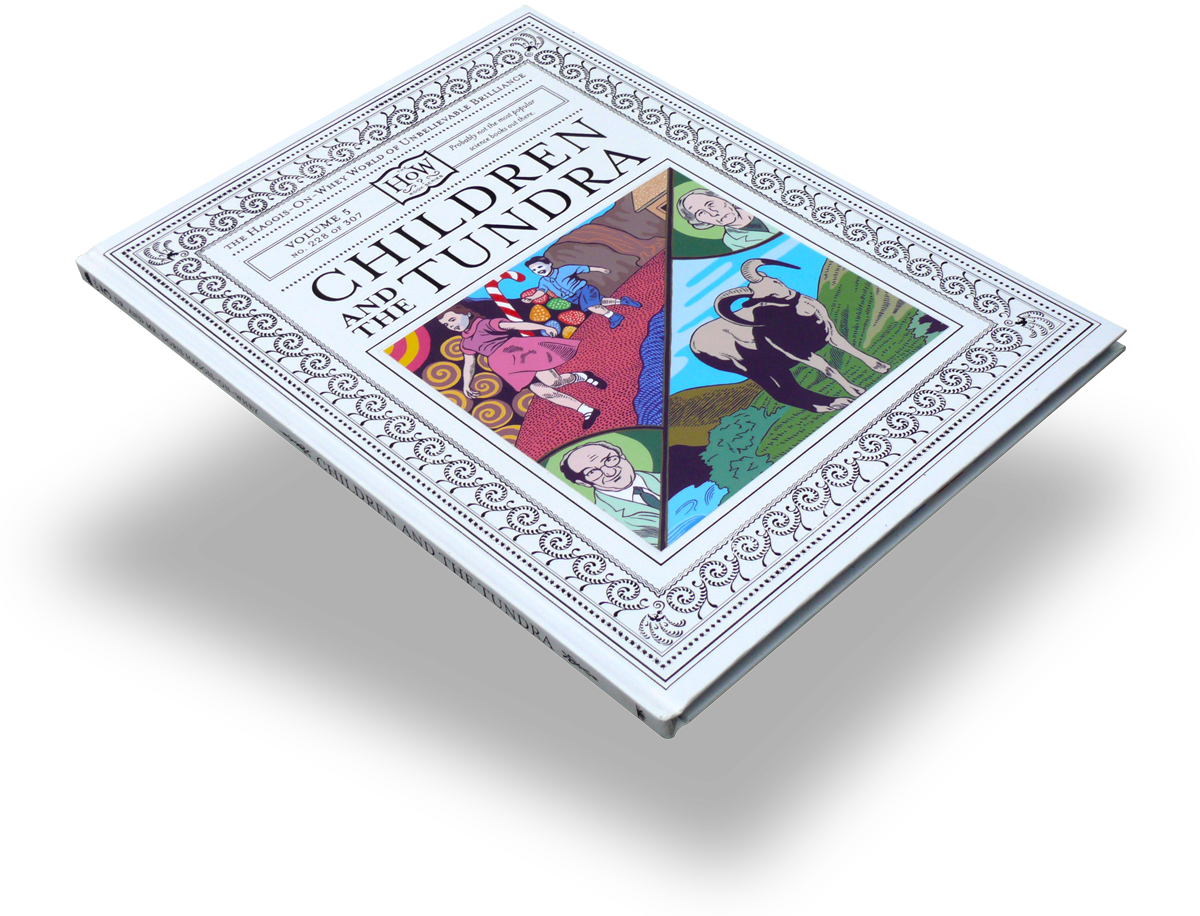

Artist’s Rendition

By Alejandro Zambra

Yasna fired the gun into her father’s chest and then suffocated him with a pillow. He was a gym teacher, and she wasn’t anything, she was no one. But she’s something now: now she’s someone who has killed, someone who sits in jail waiting for her shitty food and remembering her father’s blood, dark and thick. She doesn’t write about that, though. She only writes love letters.

Only love letters, as if that were nothing.

But it isn’t true that she killed her father. That crime never happened. Nor does she write love letters, she never has, maybe because she knows almost nothing about love, and what she does know, she doesn’t like. What she does know is monstrous. The one doing the writing is someone else, someone urgently recalling her, not because he misses her or wants to see her but simply because he was commissioned, a few months ago now, to write a detective story. Preferably one set in Chile. And right away he thought of her, of Yasna, of that crime that was never committed, and although he had dozens of other stories to choose from, some of them more docile, easier to turn into detective stories, he thought that Yasna’s story deserved to be told, or at least that he would be able to tell it.

He took a few notes at the time, but then he had to focus on other obligations. Now he has only one day left to write it.

The innocent part of the story, the least useful part, the part he won’t include, and that he doesn’t even fully remember—since his job consists, also, of forgetting, or rather of pretending that he remembers what he has forgotten—begins in the summertime, toward the end of the eighties, when both of them were fourteen years old. He wasn’t even interested in literature yet; back then the only thing that held his interest was chasing women, with timidity but also persistence. But it’s excessive to call them women—they weren’t women yet, just as he was not yet a man. Although Yasna was several times more a woman than he was a man.

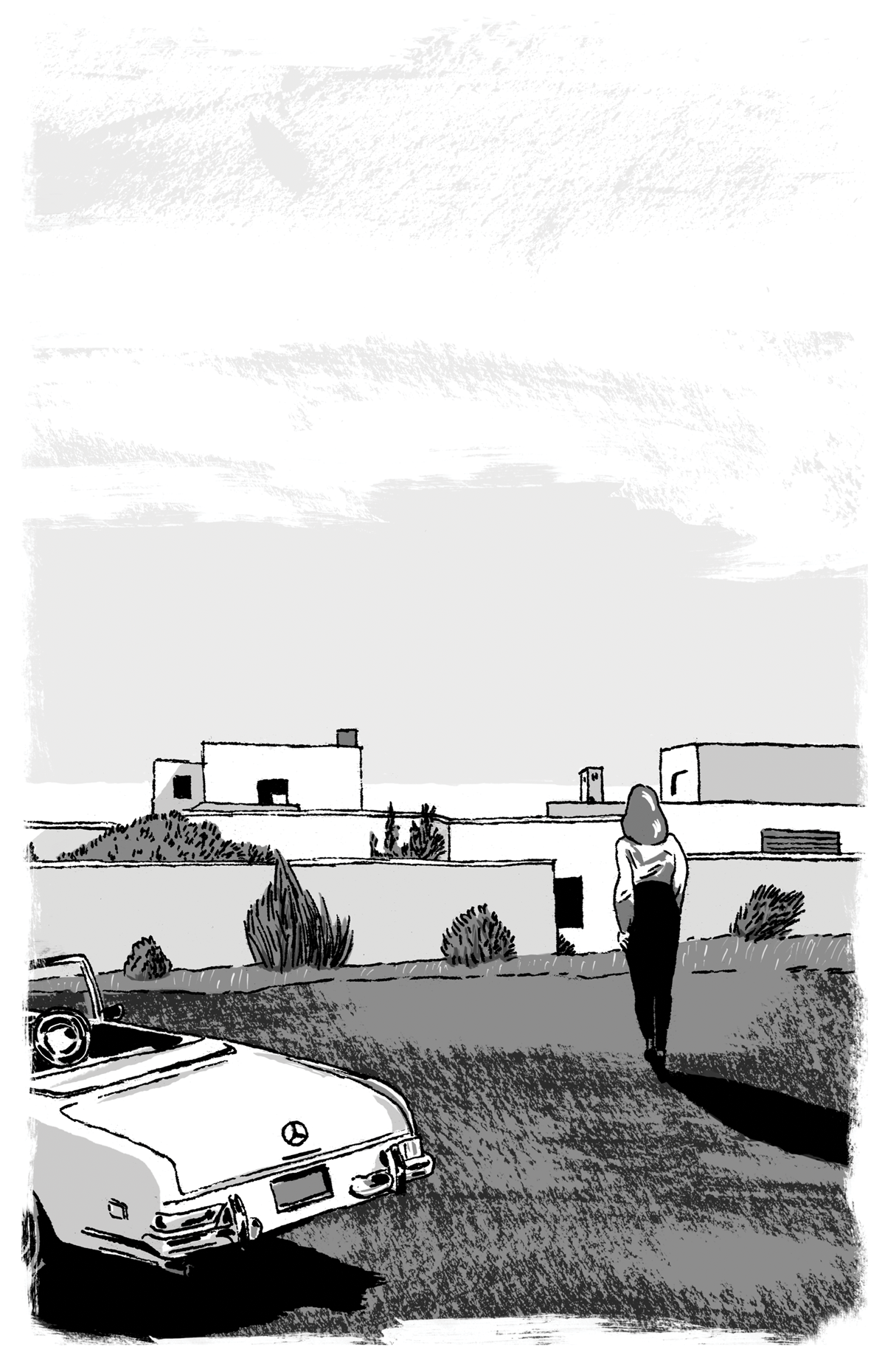

Yasna lived a few blocks away. She spent her afternoons in the messy front yard of her house, surrounded by roses, rue shrubs, and foxtails, sitting on a stool, a block of drawing paper on her lap.

“What are you drawing?” he asked her one afternoon from the other side of the fence, momentarily emboldened, and she smiled, not because she wanted to smile, but out of reflex. In reply she held up the block, and from a distance it seemed to him that there was a face sketched on the paper. He didn’t know if it was a man’s or a woman’s, but he thought he could tell it was a face.

They didn’t become friends, but they went on talking every once in a while. Two months later she invited him to her birthday party, and he, breathing happiness, going for broke, bought her a globe in the bookstore on the plaza. The night of the party he ran into Danilo, who was smoking a joint with another friend on the corner—they had a ton of weed, they’d started growing it a while ago, but they still hadn’t made up their minds to sell it. Danilo offered him the joint, and he took four or five deep drags, and straight away he felt the dulling effect that he knew well, though he didn’t smoke with any real frequency. “What’ve you got there?” Danilo asked him, and he’d been waiting for that question, hiding the bag precisely so they would ask him: “The world,” he replied with glee. They carefully undid the cellophane wrapping and spent some time searching for countries. Danilo wanted to find Sweden, but couldn’t; “Look how big that country is,” he said, pointing to the Soviet Union. They finished the joint before parting ways.

Yasna seemed to be the only one taking the party seriously. She wore a blue dress down to her knees; her eyes were lined, her eyelashes curled and darkened, and there was a shadow of shy sky blue on her eyelids. The music came from a cassette tape played end to end, one that was no longer in fashion, or that was only in fashion for the more or less fifteen guests crammed into the living room. They were clearly all good friends, they’d change partners in the middle of the songs, which they sang along to enthusiastically, though they knew absolutely no English.

He felt out of place, but Yasna looked over at him every two minutes, every five minutes, and the rhythm of those glances competed with the lethargy from the weed. After gulping down two tall glasses of Kem Piña, he sat down at the dining room table as a new cassette started to play, Duran Duran this time. No-no-notorious. They danced to it strangely, as if it were a polka, or one of those old ballroom dances. It all seemed ridiculous to him, but he wouldn’t have said no to joining in, he would have danced well, he thought suddenly, with an inexplicable drop of resentment, and then he focused on the chips, on the shoestring potatoes, the cheese cut up into uneven cubes, the nuts, and a few dozen multicolored crunchy balls that struck him, who knows why, as interesting.

He doesn’t remember the details, except for the sudden lash of hunger, the wound of hunger: the munchies. He made an effort to eat at a normal speed, but when Yasna came in with the tortilla chips and an immense bowl of guacamole, he lost control. Tortilla chips and guacamole had only recently been introduced in Chile, he had never tried them before, he didn’t even know that was what they were called, but after trying one he couldn’t stop, even though he knew everyone was watching him; it seemed like they were taking turns looking at him. He had bits of avocado on his fingers, and tomato and grease from the chips; his mouth hurt, he felt half-chewed bits of food stuck in his molars, he extricated them tenaciously with his tongue. He ate the entire bowl almost by himself, it was scandalous. And still he wanted to go on eating.

Just then the door to the kitchen opened and a white light hit him right in the face. A man looked out; he was fairly fat but brawny, his parted hair divided into two identical halves combed back with gel. It was Yasna’s father. Beside him was someone younger, very similar in appearance, you might say good-looking if it weren’t for the scar from a cleft lip, though perhaps that imperfection made him more attractive. Here ends, perhaps, the innocent part of the story: when they grab him tightly by the arm and he tries desperately to go on eating, and a few moments later, after a long and confused series of hard looks and clipped sentences, of scraping and dragging, when he feels a kick in his right thigh followed by dozens of kicks on his ass, his shins, his back. He’s on the floor, enduring the pain, with Yasna’s sobbing and some unintelligible shouts in the background; he wants to defend himself, but he barely manages to shield his groin. It’s the second man who is beating him, the one Yasna will later call the assistant. Yasna’s father stands there and watches, laughing the way bad guys laugh in lousy movies and sometimes also in real life.

Although none of this, in essence, interests him for his story, he tries to remember if it was cold that night (no), if there was a moon (waning), if it was Friday or Saturday (it was Saturday), if anyone tried, in all the confusion, to defend him (no). He puts his clothes on over his pajamas, because it’s the middle of winter and much too cold, and as he drives to the service station to buy kerosene, he thinks with confidence, with optimism, that he has all morning to work on his notes and in the afternoon he will write nonstop, for four or five hours, and then he’ll even have enough time, in the evening, to go with a friend to try out the new Peruvian restaurant that opened up near his house. He fills the gas cans and now he’s at the Esso market, drinking coffee, chewing on a ham-and-cheese sandwich, and thumbing through the newspaper he got for free for buying a coffee and a ham-and-cheese sandwich. What they want from him is simply a blood-soaked Latin American story, he thinks, and in the margins of the news he jots down a series of decisions that take shape harmoniously, naturally, like the promise of a peaceful day at work: the father will be named Feliciano and she will be Joana; the assistant and Danilo are no good, nor is the marijuana, maybe a hard drug instead, and though he doesn’t really want to make Feliciano into a drug trafficker—too hackneyed—he does think it’s necessary to move the protagonists down in class, because the middle class—and he thinks this without irony—is a problem if one wants to write Latin American literature. He needs a Santiago slum where it’s not unusual to see teenagers in the plazas cracked out or huffing paint thinner.

Nor will it work for Feliciano to be a gym teacher. He imagines him unemployed instead, humiliated and jobless at the start of the eighties, or later, surviving in the work programs of the dictatorship, endlessly sweeping the same bit of sidewalk, or turned into a snitch who informs on suspicious activity in the neighborhood, or maybe even knifing someone to the ground. Or maybe as a cop, one who comes home late and shouts for his food, and who has no qualms about threatening his daughter at night with the same billy club he used to beat back protesters at noon.

He has some doubts at this point, but they’re nothing serious. Nothing is that serious, he thinks: it’s just a ten-page story, fifteen pages tops, he doesn’t have to waste time on the backstory. Two or three resonant phrases, a few well-placed adjectives will fix any problems. He parks, takes the gas cans out of the trunk, and then, while he fills the heater’s tank, he imagines Joana splashing kerosene all over the house, with her father inside—too sensationalist, he thinks, he prefers a gun, maybe because he remembers that there was a gun in Yasna’s house, that when she said she was going to kill her father she mentioned the gun in the house.

There was a gun, of course there was, but it was only an air rifle, which had lain idle for years in the closet. It was a testament to the time when the man used to go to the country with his friends to hunt partridge and rabbit. Only once, one spring Sunday, coming back from church when she was seven years old, did Yasna see her father fire it. He was in the yard, downing a beer and taking aim with a steady hand at the kites in the sky over the park. He hit the bull’s-eye four times: the owners couldn’t understand what was happening. Yasna thought about those parents and children from other neighborhoods watching their kites founder and crash, so disconcerted, but she didn’t say anything. Later she asked him if you could kill someone with that rifle, and he answered that no, it was only good for hunting. “Though if you got the guy in the head from close up,” amended her father after a while, “you’d fuck him up pretty good.”

After the party, the writer—who at that time didn’t even dream of becoming a writer, though he dreamed about many other things, almost all of them better than being a writer—was terribly scared and didn’t make any effort to see Yasna again. He avoided the street that led to her house, all the streets that led to her house, and he didn’t go to church, either, since he knew that she went to church, and in any case this didn’t take a lot of effort because by then he had stopped believing in God.

Six years passed before their paths crossed again. He saw her by chance, in the city center. Yasna’s hair was straighter and longer; she was wearing the two-piece suit they’d given her at work. He was wearing a plaid flannel shirt and combat boots, his hair disheveled, as if he wanted to exemplify the fashion of the times—or the part of fashion that corresponded to him, a literature student. By then he could be called a writer, he had written some stories. Whether they were good or bad was not important—a writer is someone who writes, a little or a lot, but who writes, just as a murderer is someone who kills, whether they’ve claimed one person or many. And it isn’t fair to say that she was nothing, then, that she was no one, because she was a cashier at a bank. She didn’t like the work but she also didn’t think—nor does she think now—that there existed any job that she would like.

While they drank Nescafé at a diner they talked about the beating, and she tried to explain what had happened, but she said she wasn’t very clear on that herself. Then she talked about her childhood, especially about her mother’s death in a car crash, she’d barely gotten to know her, and she talked to him about the assistant, which was how her father had first introduced the man to her while they were varnishing some wicker chairs in the yard, although some days later he told her, as if it weren’t important, that actually the assistant was the son of a friend who had died, that he didn’t have anywhere to go and so he’d be living with them for a while. The assistant was twenty-four years old then, he came home late at night, he slept most of the morning, he didn’t work or study, but sometimes he babysat the little girl, mostly on Tuesdays, when Yasna’s father got home at midnight after practicing with his basketball team, and Saturdays, when her father had games and then went out with his teammates to drink a few beers. The writer didn’t understand why she was telling him all this, as if he didn’t know (and maybe he didn’t, although, by that point, since he was already a writer, he should have known) that this was the way people get to know each other, by telling each other things that aren’t relevant. By letting their words fly happily, irresponsibly, until they reach dangerous territories.

Although the conversation wasn’t over, he asked her if she had a phone, if there was some way they could see each other again, because right now he had a party to go to. She shrugged her shoulders, and maybe she was waiting for him to invite her to that party, although in any case she couldn’t go, but he didn’t invite her, and then she didn’t want to give him her number anymore. She also forbade him from showing up at her house, even though the assistant no longer lived there.

“Then how will we see each other?” he asked again, and she, again, shrugged her shoulders.

But she’d mentioned the name of the bank where she worked, which had only three branches, so he was able to track her down a few weeks later, and they began a routine of lunches, almost always at a fried-chicken place on Calle Bandera, other times at a joint on Teatinos, and also, when one of them had more money, at Naturista. He went on hoping for something more to happen, but she was elusive, she told him about a boyfriend who was so generous and understanding he seemed clearly invented. Sometimes, for long stretches, he watched her talk but didn’t listen to her. He looked most of all at her mouth, her teeth, perfect except for the stains from cigarette smoke on the front ones. He would do this until she raised or lowered her voice, or maybe let slip some unexpected bit of information, as she did one time with a sentence that, although he hadn’t the slightest idea what she’d been talking about, brought him back to the present, though she didn’t say it in the tone of a confession: on the contrary, she said it as if it were a joke, as if it were possible for a sentence like that one to be a joke. “I wasn’t happy in my childhood,” was what she said, and he didn’t understand what he should have understood, what anyone today would understand, but hearing her say it still shook him, or at least it woke him up.

Did she really use that word, so formal, so literary: childhood? Maybe she said “when I was a kid,” or “when I was little.” Whatever she’d said, one would have had to tell the entire story, years ago, cultivating a sense of mystery, taking care with one’s dramatic effects, building up gradual, shocking emotion. Good writers and also the bad ones knew how to do this, it didn’t seem immoral to them, they even enjoyed it, to the extent that depicting a story always brings a certain kind of pleasure. But what would that mystery be good for now, what kind of pleasure could be gained when the sentence that says it all has already been let loose? Because there are some phrases that have won their freedom: phrases we have learned how to hear, to read, to write. Fifteen, thirty years back, good writers, and bad ones too, would have trusted in a sentence like that to awaken a mystery that they would reveal only at the end, with a scene of the father asleep and the assistant in the bedroom touching the nipples of a ten-year-old girl, who is surprised but, as if it were a game of Monkey See, Monkey Do, puts her own hand under the assistant’s shirt and, with utter innocence, touches his nipple back.

Another scene, two days later. The father is at basketball practice and the assistant calls her into his room, closes the door, takes off her clothes, and leaves her locked in there. The girl doesn’t resist, she stays there, she searches among his clothes, which are still in bags as if, though he’s lived there for months now, he had just arrived or were about to leave—the girl tries on shirts and some enormous blue jeans, and she’s dying to look at herself in the mirror, but there’s no mirror in the assistant’s room, so she turns on a little black-and-white TV on the nightstand, and there’s a drama on that isn’t the one she watches, but the knob spins all the way around and she ends up getting sucked into the plot anyway, and that’s where she is when she hears voices in the living room. The assistant appears with two other guys and he takes the clothes she’s found off her, threatens her with the bottle of Escudo beer he has in his left hand, she cries and the guys all laugh, drunk, on the floor. One of them says, “But she doesn’t have any tits or pubes, man,” and the other replies, “But she’s got two holes.”

The assistant doesn’t let them touch her, though. “She’s all mine,” he says, and throws them out. Then he puts on some grotesque music, Pachuco, maybe, and orders her to dance. She’s crying on the floor like she would during a tantrum. “I’m sorry,” he consoles her later, while he runs his hand over the girl’s naked back, her still shapeless ass, her white toothpick legs. That day in his room he puts two fingers inside her and pauses, he caresses her and insults her with words she has never heard before. Then he begins, with the brutal efficiency of a pedagogue, to show her the correct way to suck it, and when she makes a dangerous, involuntary movement, he warns her that if she bites it he’ll kill her. “Next time you’re gonna have to swallow,” he tells her afterward, with that high voice some Chilean men have when they’re trying to sound indulgent.

He never ejaculated inside her, he preferred to finish on her face, and later, when Yasna’s body took shape, on her breasts, on her ass. It wasn’t clear that he liked these changes; over the five years that he raped her, he lost interest, or desire, several times. Yasna was grateful for these reprieves, but her feelings were ambiguous, muddled, maybe because in some way she thought she belonged to the assistant, who by that point didn’t even bother to make her promise not to tell anyone. The father would come home from work, fix himself some tea, greet his daughter and the assistant, then ask them if they needed anything. He’d hand a thousand pesos to him and five hundred to her, and then he’d shut himself in for hours to watch the TV dramas, the news, the variety show, the news again, and the sitcom Cheers, which he loved, at the end of the lineup. Sometimes he heard noises, and when the noises became too loud he got some headphones and connected them to the TV.

It was precisely the assistant who urged Yasna to organize her fifteenth birthday party (“You deserve it, you’re a good girl, a normal girl,” he told her). At that point he’d been disinterested for several months; he would only touch her every once in a while. That night, however, after the beating, when it was already almost dawn, drunk and with a pang of jealousy, the assistant informed Yasna, in the unequivocal tone of an order, that from then on they would sleep in the same room, that now they would be like man and wife, and only then did the father, who was also completely drunk, tell him that this was not possible, that he couldn’t go on fucking his sister—the assistant defended himself by saying she was only his half sister—and that was how she found out they were related. Completely out of control, his eyes full of hate, the assistant started to hit Yasna’s father, who as she knew from then on was also his father, and even gave Yasna a punch on the side of her head before he left.

He said he was leaving for good and in the end he kept his word. But during the months that followed she was afraid he would return, and sometimes she also wanted him to come back. One night she went to sleep with her clothes on, next to her father. Two nights. The third night they slept in an embrace, and also on the fourth, the fifth. On night number six, at dawn, she felt her father’s thumb palpating her ass. Maybe she shed a tear before she felt her father’s fat penis inside her, but she didn’t cry any more than that, because by then she didn’t cry anymore, just as she no longer smiled when she wanted to smile: the equivalent of a smile, what she did when she felt the desire to smile, she carried out in a different way, with a different part of her body, or only in her head, in her imagination. Sex was for her still the only thing it had ever been: something arduous, rough, but above all mechanical.

The writer eats some cream of asparagus soup with half a glass of wine for lunch. Then he sprawls in an armchair next to the stove with a blanket over himself. He sleeps only ten minutes, which is still more than enough time for an eventful dream, one with many possibilities and impossibilities that he forgets as soon as he wakes up, but he retains this scene: he’s driving down the same highway as always, toward San Antonio, in a car that has the driver’s seat on the right, and everything seems under control, but as he approaches the tollbooth he’s invaded by anxiety about explaining his situation to the toll collector. He’s afraid the woman will die of fright when she sees the empty seat where the driver should be. The volume of that thought rises until it becomes deafening: when she sees that nobody is driving the car, the toll collector—in the dream it’s one woman in particular, one he always remembers for the way she has of tying back her hair, and for her strange nose, long and crooked, but not necessarily ugly—will die of fright. “I’m going to get out quickly,” he thinks in the dream. “I’ll explain.”

He decides to stop the car a few meters before he reaches the booth and get out with his hands up, imitating the gesture of someone who wants to show he isn’t armed, but the moment never takes place, because although the booth is close, the car is taking an infinite amount of time to reach it.

He writes the dream down, but he falsifies it, fleshes it out—he always does that, he can’t help but embellish his dreams when he transcribes them, decorating them with false scenes, with words that are more lifelike or completely fantastic and that insinuate departures, conclusions, surprising twists. As he writes it, the toll collector is Yasna, and it’s true that in an indirect, subterranean way, they are similar. Suddenly he understands the discovery here, the shift: instead of working at a bank, Joana will be a collector in a tollbooth, which is one of the worst possible jobs. He pictures her reaching out her hand, managing to grab all the coins, loving and hating the drivers or maybe completely indifferent. He imagines the smell of the coins on her hands. He imagines her with her shoes off and her legs spread apart—the only license she can take in that cell—and later on an inter-city bus, on her way home, dozing off and planning the murder, now really convinced that it is, as they say in Mass, truly right and just. After she’s done it she heads south, sleeps in a hostel in Puerto Montt, and reaches Dalcahue or Quemchi, where she hopes to find a job and forget everything, but she makes some absurd, desperate mistakes.

The last time he saw Yasna, they almost had sex. Up until then they’d seen each other only during those lunches in the city center; whenever he’d asked her to go to the movies or out dancing she’d pile on the excuses and talk vaguely about her perfect, made-up boyfriend. But one day she called him, and then she showed up at the writer’s house. They watched a movie and then they planned to go to the plaza, but halfway there she changed her mind, and they ended up at Danilo’s, smoking weed and drinking burgundy. The three of them were there, in the living room, high as kites, stretched out on the rug, uncaring and happy, when Danilo tried to kiss her and she affectionately pushed him away. Later, half an hour, maybe an hour later, she told them that in another world, in a perfect world, she would sleep with both of them, and with whoever else, but that in this shitty world she couldn’t sleep with anyone. There was weight in her words, an eloquence that should have fascinated them, and maybe it did, maybe they were fascinated, but really they just seemed lost.

After a while Danilo let out a laugh, or a sneeze. “If you want a perfect world, smoke another one,” he told her, and he went to his room to watch TV. Yasna and the writer stayed in the living room, and even though there was no music, Yasna started to dance, and without much preamble she took off her dress and her bra. Astonished as he was, he kissed her awkwardly, he touched her breasts, caressed her between her legs, he took off her underwear and slowly licked the down on her pubis, which wasn’t black like her hair, but brown. But she got dressed again suddenly and apologized, she told him she couldn’t, she said she was sorry, but it wasn’t possible. “Why not?” he asked, and in his question there was confusion but there was also love—he doesn’t remember it, he would be incapable of remembering it, but there was love.

“Because we’re friends,” she said.

“We’re not such great friends,” he answered, completely serious, and he repeated it many times. Yasna let out a peal of beautiful, stoned laughter, a real and delicious guffaw that only very gradually wore itself out, that lasted ten minutes, fifteen minutes, until finally she managed to find, with difficulty, the way back to a serious and resonant tone with which it would be appropriate to tell him that this was a good-bye, that they could never see each other again. He didn’t understand, but he knew it didn’t make sense to ask any questions. They sat with their arms around each other in a corner. He took Yasna’s right hand and calmly began to bite and eat her fingernails. He doesn’t remember this, but while he looked at her and bit her fingernails he was thinking that he didn’t know her, that he would never know her.

Before they left they sat for a while with Danilo, in front of the TV, to watch an eternal game of tennis. She drank four cups of tea at an impressive speed, and she ate two marraqueta rolls. “Where’s your mom?” she asked Danilo suddenly.

“Over at an aunt’s house,” he answered.

“And where’s your dad?”

“I don’t have a dad,” he answered. And then she said:

“You’re lucky. I do have one. In my house there’s a rifle and I’m going to kill my father. And I’m going to go to jail and I’m going to be happy.”

By now it’s three in the afternoon, he doesn’t have much time left. He urgently turns on the computer, annoyed by the seconds the system takes to start up. He writes the first five pages in a matter of minutes, from the moment the detective arrives at the scene of the crime and realizes he has been there before, that it’s Joana’s house, until he climbs up to the attic and finds the old boxes with clothes from the time when they were a couple, because in the story they were a couple, but not for very long, and in secret. He also finds the globe he’d given her—but without the stand that held it—and a backpack he thinks he recognizes in among the fishing rods and reels, the buckets and shovels for the beach, the sleeping bags and rusted dumbbells. He keeps looking around, impelled more by nostalgia than a desire to find evidence, and then, just like in books, in movies, and also sometimes in reality, he finds something that would not be conclusive to anyone else, but that is, immediately, to him: a box full of drawings, hundreds of drawings, all portraits of her father, ordered by date or series, but each more realistic than the one before, at first sketched in pencil, and then, the majority, in the green ink of a Bic pen, fine point. When he sees the accentuated contours, gone over so many times that the paper is often torn, and when he notices the exaggeration of the features—though never to the point of caricature, they never lose the aura of realism—the detective understands what he should have understood a long time before, what he hadn’t known how to read, what he hadn’t known how to say, hadn’t known how to do.

The writer works at a cruising speed through the intermediate scenes, and takes great pains over the final two pages, when the detective finds Joana in a boarding house in Dalcahue and promises he will protect her. She tells him in great detail about the crime, put off so many times over the course of her life, and while she cries she seems to grow calmer. Maybe they stay together, in the end, but it’s not certain. The ending is delicate, elegantly ambiguous, though it’s not clear what it is the writer thinks is ambiguous, or delicate, or elegant about it.

It’s not a great story, but he sends it off with a clear conscience, and he even has time to drink a pisco sour and eat some yucca a la huacaína before his friends get to the Peruvian restaurant.

It’s not a great story, no. But Yasna would like it.

Yasna would like the story, though she doesn’t read, she doesn’t like to read. But if it were made into a movie, she would watch it to the end. And if she caught a repeat of it and she didn’t remember it, or even if she remembered it well, she would watch it again. She doesn’t often watch movies, in truth, nor does she often recall the writer. She doesn’t even know he is a writer. She did remember him a few months ago, though, when she was walking in the neighborhood where he used to live.

They had declared her father terminally ill, and recommended she give him marijuana to help with the pain. She’d thought of Danilo’s plants, hence that walk through the old neighborhood, which seemed erratic but was not: she enjoyed the luxury of walking around aimlessly, peripherally, even reaching the end of a street and then retracing her steps, as if she were searching for an address. But she knew perfectly well where Danilo lived, still in his family home; she merely wanted to enjoy that luxury, modest as it was. Her father was sleeping more calmly by then, with less pain than on previous days, so she could go out for a walk and take her time.

“I hope you haven’t killed your father,” he said to her when he finally recognized her, and since she didn’t remember her words from that night almost twenty years before, she looked at him with alarm. Then she remembered her plan, the air rifle, and that crazy afternoon. She felt an uncomfortable happiness when she remembered those lost details, as Danilo talked and cracked jokes. She liked that house, the atmosphere, the camaraderie. She stayed for tea with Danilo, his wife, and their son, a dark-skinned, long-haired boy who spoke like an adult. The woman, after looking at Yasna intensely, asked her what she did to stay so thin.

“I’ve always been thin,” she answered.

“Me too,” said the boy. She bought a lot of marijuana, and Danilo also threw in some seeds.

It’ll be a while before the plant flowers. She is watering it now while she listens to the news on the radio. Her father doesn’t rape her anymore, he wouldn’t be able to. She hasn’t forgiven him, she’s reached a point where she doesn’t believe in forgiveness, or in love, or in happiness, but maybe she believes in death, or at least she waits for it. While she moves the furniture around in the living room, she thinks about what her life will be when he dies: it’s an abstract feeling of freedom, maybe too abstract, and for that reason uncomfortable. She thinks of an ambiguous pain, of a disaster, calm and silent.

She hears her father’s complaints coming from the kitchen, his degraded, corrupted voice. Sometimes he shouts at her, berates her, but she pays him no mind. Other times, especially when he is high, he laughs his labored laughter, utters disjointed phrases. She thinks about the will to live, about her father clinging to life, who knows what for. She brings him another marijuana cookie, turns on the TV for him, puts his headphones on for him. She stays awhile beside him, looking at a magazine. “I didn’t believe in God, but only with his help could I overcome the pain,” says a famous actor about his wife’s death. “It’s simple: lots of water,” says a model on another page. “Don’t let public tantrums get to you.” “It’s her second TV series so far this year.” “There are many ways to live.” “I didn’t know what I was getting mixed up in.”

She hears the trash collector going by, the men’s shouts, the dog barking, the whisper of canned laughter coming from the headphones, she hears her father’s breathing and her own breathing, and all those sounds don’t alter her feeling of silence—not of peace: of silence. Then she goes to the living room, rolls herself a joint, and smokes it in the darkness.